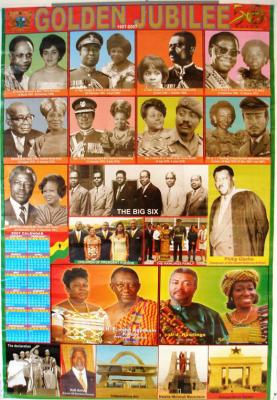

On 6 March 1957, Ghana became the first country in Sub-Saharan Africa to achieve independence from its colonial masters. Ever since, Independence Day has been celebrated, and particularly the decennial celebrations have provided opportunities for taking stock, reflecting on past achievements and setting out national aims. But all Ghanaians regard ‘Ghana@50’, as the official orthography would have it, as a special occasion that evokes both pride and critical reflection. ‘Championing African excellence’, the celebration’s official motto printed on numerous flags, festival cloth, t-shirts, coffee cups and the like, reflects Ghana’s self-confidence vis-à-vis other African nations. Ghanaians are proud their country was once a leading advocate of African independence and pan-Africanism, that it currently figures prominently as one of Africa’s few stable multi-party democracies and that it is currently playing a pioneering role in the African peer review mechanism of the New Partnership for Africa’s Development (NPAD) initiative. And when Ghana’s president J. A. Kufuor was elected Chairman of the African Union in January 2007, it was yet another tribute to Ghana’s pre-eminent standing on the continent.

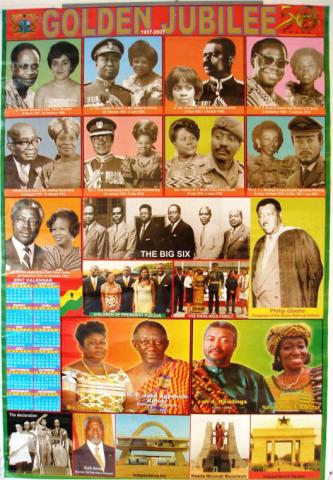

Celebrating national events such as the Jubilee of Ghanaian independence provokes public discussion regarding the content and meaning of national values, shared experiences and socio-political unity. The celebrations become an important arena in which the state makes the nation manifest in the hearts and minds of its citizens. The entire Jubilee year is marked by manifold commemorative events sponsored by the government, civic associations, and private businesses. Each month is assigned a particular theme, ranging from ‘Reflections’ and ‘Towards Emancipation’ to ‘Heroes of Ghana’, ‘African Unity’, ’Diaspora’ and ‘Service to the Nation’. Activities include the theatrical re-enactment of relevant historical events, the inauguration of new monuments, the renovation of the birth places of the Ghanaian ‘fathers’ of independence, performances of classical and modern Ghanaian plays, film presentations, art exhibitions, book launches, festivals of ‘traditional’ culture, parades, a ‘Rally round the Flag’ campaign, political speeches and academic conferences, a ‘Miss Ghana@50’ beauty contest, and much more.[2]

However, much as these events have sparked popular enthusiasm and were applauded by the media, the Jubilee’s organisation has also provoked heated debates over how inclusive and truly ‘national’ the official celebrations are and how the nation’s fiftieth anniversary should be appropriately commemorated. The controversies centre on three main issues. First, political inclusiveness, which concerns, among other issues, the question who precisely should organise, finance and lead the celebrations − a government body (as is currently the case), a committee comprised of representatives from all political parties, or an ‘a-political’ organisation that includes, among others, chiefs and representatives from various professional associations. The second point of contention regards the celebrations’ social inclusiveness, i.e. the extent to which the symbols, performances and festivities address the ‘grass-roots’, or mostly the (political) elite. For instance, in the media a debate arose as to whether there was indeed anything to celebrate at all and, more substantially, if the money for the Jubilee would not be better spent investing in social infrastructure and poverty reduction. Finally, the third controversy concerned the ethnic and regional inclusiveness, i.e. how evenly Jubilee events and funds were geographically distributed and to which degree all regions and ethnic groups could identify with the festivities’ symbols and slogans. The Ghana@50 secretariat tried to organise events that demonstrated national unity, or, as Ghana’s favourite slogan has it: ‘unity in diversity’. But Akan-centred symbols abounded, at least in the eyes of non-Akan onlookers. The 0 in the Ghana@50 sign, for instance, is clearly styled as an Akan adinkra symbol, signifying gye nyame, ‘only God’; the official Jubilee cloth is based on a kente design; and Northerners, wearing the smock as their ‘traditional’ dress, felt slighted by the Jubilee secretariat’s attempt to declare the kente cloth as the article of clothing constituting official ‘Ghanaian’ traditional dress that everybody was expected to sport on Independence Day.

More generally, celebrations such as the Golden Independence Jubilee constitute dense moments of the symbolic, ritual and discursive construction of nationhood. They both consolidate and at the same time redefine the nation by on the one hand enhancing citizens’ emotional attachment to it, and on the other hand by providing an opportunity for vigorous debates regarding national history, current achievements and problems, and visions for the future. The celebrations – by virtue of the way they are organised and the debates this provokes − therefore represent excellent opportunities for research into the challenges of nation-building and for examining competing or consensual images of nationhood.

In this paper, however, we will not (yet) engage in an in-depth analysis of these challenges and ongoing debates, but rather present a first-hand account of our observations during the festivities around March 5 and 6 in Accra, where we were privileged to be admitted to some of the official (and unofficial) celebrations. Given that it was practically impossible to observe ‘the’ festivities in any truly comprehensive way, we decided on the following strategy: the choice of events to be observed was not to be determined by our own interests or inclinations, nor by the serendipity of the course of events, but rather by selected Ghanaian ‘participant-observers’ or ‘informants’ whose movements, comments and encounters we would follow as closely as possible for the duration of Independence Day. In order to gain a more nuanced and pluralised perspective, particularly given the political nature of the celebrations, we opted to follow one member of the ruling New Patriotic Party (NPP) and one member of parliament from the opposing National Democratic Congress (NDC). Because we felt that it would be difficult to expect complete strangers to accept our company for an entire day, and particularly this very special day, we decided to ask Ghanaian friends and adopted family with whom one of the authors (Carola Lentz) had become acquainted during the many years spent conducting research in Ghana’s Upper West Region. We were aware that this could result in a ‘Northern’ bias, but given the debates on regional inclusivity of the celebrations, we felt that this perspective could prove particularly interesting.

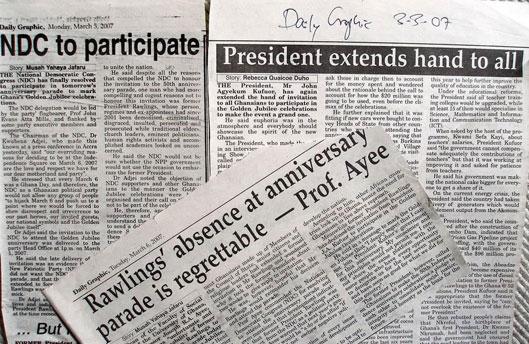

In the end, however, things did not quite work out the way we had planned. This had much to do with the fact that up until nearly last minute, the NDC had not decided whether to boycott or participate in the official celebration on March 5 and 6. The opposition had boycotted the parliamentary sessions for nearly two weeks in February, including the day of the President’s ‘State of the Nation’ address, as a gesture of solidarity with Daniel Abodakpi, an NDC member of parliament and former Minister of Trade who had been accused of corruption and was convicted to ten years in prison. The NDC castigated the trial as ‘a travesty of justice’,[3] and it was only during the first days of March that the NDC finally agreed to participate in the Golden Jubilee Parade, after a number of reconciliatory meetings which some elder statesmen, including former Secretary General of the United Nations Kofi Annan held with government and opposition representatives. Only Rawlings himself remained adamant that he personally would not participate because the same incumbent government which had unconstitutionally withdrawn the courtesies that were his due as former Head of State now wanted to invite him to the celebration in precisely that capacity. He felt compelled to ask ‘what is being celebrated?’ and did not want to risk, after all that had happened, any further humiliation.[4] As a result ‘our’ NDC parliamentarian, who serves as ex-Head of State’s solicitor and spokesman-of-sorts, had to support Rawlings in attending to the numerous visitors and international journalists who wanted to hear his views on Ghana’s anniversary and political future. In this setting our presence was not opportune. What we were ultimately able to follow will be explained below. But it is interesting to note how the limitations to which our research was subject in practice are indicative of ongoing debates.

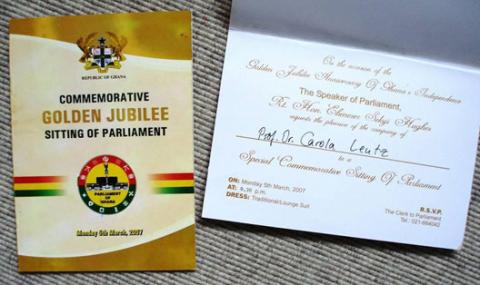

The Golden Jubilee Sitting of Parliament, 5 March 2007

For the evening of March 5, the Jubilee secretariat scheduled a commemorative Golden Jubilee Sitting of Parliament that was to re-enact the historical final session of the colonial Legislative Assembly in 1957, which the Duchess of Kent had graced with her presence, representing Queen Elizabeth II. Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah, supported by the Deputy Leader of the Opposition S. D. Dombo, spoke about the bright future of an independent Ghana and thanked Britain and other countries for their support of the new nation. The Speaker of Parliament then read the Governor’s message to terminate the Legislative Assembly by royal prerogative and announced that the body would reconvene as the newly independent Parliament the next morning. This was followed by the declaration of Independence at midnight by Kwame Nkrumah and his close supporters on the Old Polo Grounds across Parliament House,[5] the lowering of the Union Jack and the raising of the new Ghanaian flag. On the morning of March 6, in the presence of many foreign dignitaries, the Duchess of Kent opened the First Session of the Parliament of Ghana, conveyed the Queen’s greetings to the Governor, the Speaker, the members of parliament and to the people of Ghana and presented the Prime Minister the Ghana Independence Act and Ghana’s Constitution. The Prime Minister then moved, this time seconded by Leader of the Opposition K. A. Busia, to send an address to the Queen on behalf of the House, and Parliament was adjourned indefinitely. Following the re-enactment of this sitting, a grand parade and other festivities were held throughout Accra and all over the country. [6]

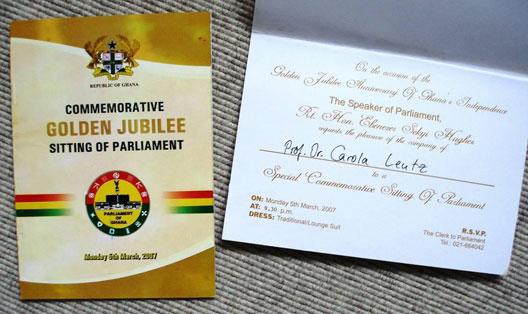

Historically, then, Parliament always played a central role in the independence celebrations, not least because Nkrumah as Prime Minister was himself once Member of the Legislative Assembly. Under his regime, however, the constitution was changed in favour of a presidential system, a system that by and large also characterises Ghana’s current government and that presents new challenges for the balance of power between the legislative and executive branches. One of the controversies during the Jubilee was how to re-enact the historical session in the absence of a prime minister, and, even more importantly, how much decision-making power Parliament would retain over the staging of the Commemorative Session when this session was, in reality, largely planned by members of the executive (among them, the Jubilee secretariat). This controversy – an example of the above mentioned debates regarding political inclusivity − was forcefully brought home to us quite early in our research when we attempted to secure our admission to the event.

We had, quite well in advance of the festivities, applied for press accreditation, which we were finally granted. But the press ID did not automatically award access to the more restricted events, and various newspaper announcements left no doubt that admission to the parliamentary session was ‘by invitation only’. Our parliamentarian friend was not aware of these regulations, and fumed when head of Parliamentary protocol told him that all matters of procedure and security had been taken over by the ‘Castle’.[7] In the end, however, after countless phone calls and with assistance from the Minority Chief Whip, he was able to arrange for two invitations, which had to be picked up before 4:00 pm.

Having to set out so early, this left us sufficient time to wander around the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park, formerly the Old Polo Grounds, before Parliament went into session. At 4:00 pm, according to the official Jubilee programme published in all the papers, David Dontoh, a well-known Ghanaian actor, was to re-enact Kwame Nkrumah’s declaration of Independence. We were rather puzzled by the rather ‘unhistorical’ time, and, in fact, despite the official programme there was no performance that afternoon. When we arrived at the site, all we could see were numerous helpers busy setting up the benches, chairs, podia and audio equipment for the gala and rock concert that evening. A Dutch water engineer explained that he and his crew would probably not be able to fill the pools and fountains at the mausoleum in time, even though the water supply in several parts of the city had been cut several days previously to ensure sufficient water to fill the ditches on the festival grounds – an example of the above-mentioned tensions between the ‘grass-roots’ and the elite during the Jubilee’s planning.

More generally, many of preparations for ‘the big day’ were only tackled at the last minute. Although sprightly television spots featuring historical film footage of the declaration of Independence and a specially composed song ‘Ghana is 50! Ghana! Congratulations, Ghana! Let’s all celebrate...’ had been running regularly since the beginning of the year, there was not much further evidence of the much touted festive atmosphere. The Jubilee cloth only was available for purchase beginning in early March, and it was only then that street hawkers began to peddle their flags, cups, t-shirts, pins and other printed goods. The national flags lining the streets and festooning public buildings were put up only a few hours before the arrival of the international guests of honour. The same applied to Ghana’s second biggest city, Kumasi, where people complained that the streets were ‘bare and free of Ghana flags until March 5’.[8] The National Disaster Management Organisation explained that officials and private persons hesitated to hoist flags in the streets since most of them were soon stolen.[9] However, for the NDC this was simply further proof that the people really saw no reason to celebrate.

Nevertheless, we did witness a display of sorts, almost hidden, at the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park: Nkrumah’s son, Dr Francis Nkrumah, accompanied by his family and a small group of journalists, placed a wreath at the statue of his father. That this very personal act of commemoration was of little outside interest and that it took place in absence of government officials seemed to confirm the critique voiced repeatedly by the ‘real’ Nkrumahists during the previous weeks, namely that the NPP-Government, whose political roots are embedded in the former Nkrumah opposition associated with J. B. Danquah, K. A. Busia and S. D. Dombo, was only half-heartedly paying tribute to the legacy and the person of Kwame Nkrumah. So who are the ‘heroes’, which were to be remembered and honoured for their efforts towards Ghana’s independence? And who is to be regarded as the legitimate heir to the Nkrumah legacy? A common view is that it certainly is not the NPP. But can the NDC really make this assertion, Rawlings’ attempts to make it concrete by constructing the Nkrumah Mausoleum notwithstanding? Ideological claims to this heritage were in any case made against the NPP as well as the NDC by the smaller Nkrumahist parties (CPP, PNC and other splinter groups). These controversies constitute the subtext to many publications, lectures, conferences and commemorative speeches, and it was also quite manifest in the almost private nature of Nkrumah’s son’s wreath-laying.

The debate over who were the heroes of independence to be honoured involved not only the historical rivalry between the CPP and UP and its present-day successors, but also the rift between the marginalised North and Ghana’s politically better represented South. North-South tensions became apparent in the furor provoked by the speech of the Leader of the Opposition, the lawyer Alban Bagbin from the Upper West Region, at the end of the historical parliamentary session. For reasons which we cannot go into here, the NPP is generally regarded to be an ‘Akanised’ party, while the parliamentary opposition is predominated by Northerners.[10] During the Commemorative Session of Parliament these differences were quite apparent, particularly with regard to the dress code: on the side of government most MPs wore the colourful kente cloth, while on the opposition side blue and white or black and white striped smocks or the long boubous worn by Muslims predominated.

The event in general was quite exclusive. Besides the diplomatic corps and a few journalists we were almost the only whites admitted, since sufficient room was needed in the relatively small public gallery to seat foreign dignitaries, selected heads of government departments and a few political veterans as well as living witnesses of the first Independence Day. Seated on the dais to the right of President Kufuor was the Queen of England’s official representative, the Duke of Kent (one of the sons of the self-same Duchess of Kent who had addressed the first session of the Ghanaian Parliament in 1957), and the African guest of honour, the Nigerian President Olusegun Obasanjo. To the left was seated the Speaker of Parliament, Ebenezer Begyina Sekyi-Hughes, and the Vice-President of Ghana, Alhaji Aliu Mahama, as well as the President of the Pan-African Parliament, Gertrude Ibengwe Mongella. After the speaker opened the session, short addresses were given by the President of the Pan-African Parliament, the President of Nigeria ‘on behalf of colleague Heads of State’, by the Duke of Kent and finally by President Kufuor, congratulating the nation on fifty years of independence and a relatively long and stable democratic tradition. When the Majority Leader, Felix Owusu-Adjapong, at last unceremoniously moved to adjourn, Leader of the Opposition Bagbin stepped forward to second the motion and used his control of the floor to deliver a long-winded statement to which the majority party responded with much commotion, although it was hard to determine whether this were in protest or in support. Bagbin not only welcomed Busumuru Kofi Annan, whose presence none of the previous speakers had mentioned, but also pointed out that the motion to prorogate Parliament fifty years previously was seconded, not by the Asante politician K. A. Busia whom President Kufuor had acknowledged in his commemorative speech, but by S. D. Dombo, a chief and politician from the Upper West Region. Moreover, Bagbin, in a populist move that indirectly accused the NPP Jubilee organisers of elitism, thanked ‘all Ghanaians for their patience and mandate for us to be here to represent their interests’. The rest of his statement was drowned out by the NDC faction’s tumultuous applause, and a number of NPP members waved their flags in both agreement and revelry. It is also possible that they were grateful to Bagbin that his statement indirectly protested the executive’s co-optation of Parliament. As our parliamentarian friend later commented, the executive’s choreography of the commemorative sitting, that we would not be properly re-enacting the historical experience, that there would be no exchange between both sides of the House, ... this style, for some of us, creates a lot of difficulties for the very parliamentary independence that we want. If another arm of government finds itself around another arm of government [i.e. when the executive comes to parliament], it should be seen playing a second fiddle. But what we were witnessing was that the executive arm of government together with their guests were taking centre stage in what was going on.

After the historic session our friends, and we too for that matter, were too exhausted to brave the havoc in the streets through which we would have to battle our way in order to reach Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park. From Legon Hill on the university campus we were able to see the extravagant midnight fireworks – similar displays were to take place simultaneously in all regional capitals – and the next day we read the newspaper reports about the re-enactment of the Declaration of Independence in the presence of the President and international guests. [11]

Our NDC ‘informant’ told us that night that he would have to assist Rawlings the following day in meetings with the former Head of State’s foreign friends. He recommended instead that one of us accompany the Leader of the Opposition, Alban Bagbin, who, along with other members of the faction, was to participate in the Golden Jubilee Parade.

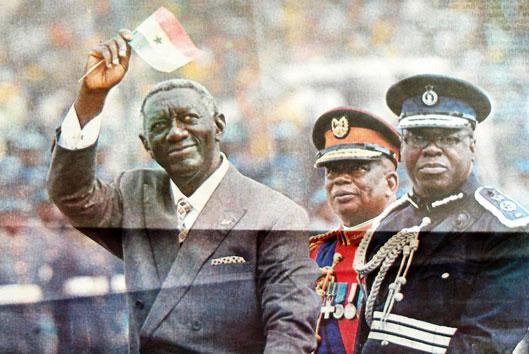

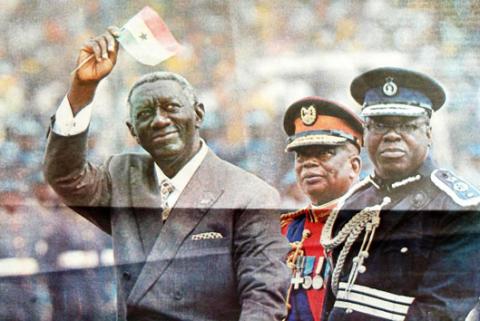

The Golden Jubilee Parade, 6 March 1957: the official celebration at Independence Square

At 7:00 am I (Carola Lentz) met the Leader of the Opposition, Alban Bagbin, at his office in Parliament, ready to set off for Independence Square, where the Jubilee Parade was to commence at 9:00 am with the entrance of the President and his guests of state. Because the street leading from Parliament House to Independence Square was already totally blocked by traffic, Bagbin’s official car could no longer bring us to the grandstand, but had to leave us at the edge of Independence Square. His body guard steered us through the crowds, right across the square, where thousands of people had been camping out since midnight in order to secure a good spot. A group of NDC supporters seem to have recognised Bagbin and cheered him on. Otherwise, it was quite clear to Bagbin and other members of the NDC, who were to later comment on the events, that the supposedly enthusiastic masses had not assembled of their own accord. Instead, during the night, the Jubilee Secretariat had carted them on busses into the city from the surrounding provinces in order to avoid the potential fiasco of half-empty stands that would expose the government’s unpopularity in front of its official guests and the press.[12] Unsurprisingly, supporters of the ruling party viewed things differently, and later descriptions of the enthusiastic masses filled the media. Be that as it may, police and security forces clearly had difficulty in securing the seating reserved for VIPs and other official guests. At the same time it was just as undesirable to have broadcast round the world images of police and security forces beating citizens with clubs, which meant that many of the official guests (civil servants, heads of departments, etc.) were only able to find seating with great difficulty, the exception being ‘VVIPs’, who were able to present an invitation to sit in one of the levels of the Presidential Arch at Independence Square.

Bagbin assumed he was also to sit with the guests of honour, since the highest government authorities and members of Parliament – the Speaker of Parliament and the Majority Leader − would no doubt also be sitting there (whether this was actually so, I was not able to verify). However, at the bottom of the stairwell security guards and ushers had been posted, and they granted permission to go upstairs only to those able to present an invitation. But Bagbin did not have one. His response − ‘I don’t need an invitation, I am the Leader of the Opposition’ – did not impress the security guards, who apparently did not even recognise him from his picture on television. Did their recalcitrance have something to do with his disregard for the government’s staging instructions during the Commemorative Sitting of Parliament the night before? Yet, we were not the only ones turned away at the entrance to the VIP section: the Chief Imam of Accra, several other Members of Parliament and other prominent political actors tried to negotiate entry or protested loudly about the (lack of) seating arrangements and further shortcoming of the organisation. Why had government entreated the opposition not to boycott the festivities only to treat them now in such a discriminatory manner? Bagbin remained calm: the security guards were only doing their job and were not responsible for the organisation. To me he stated that in his eyes this was part of the government’s strategy to humiliate the opposition party, and that Rawlings had been right not to attend the Parade. As for himself, he would not tolerate to such pettiness or try to gain access through informal channels. Instead, he would return to Parliament House and get some work done. In the eyes of the NDC critics with whom I spoke subsequently this decision amounted to a practical boycott: according to them Bagbin was only waiting for an excuse to accuse the NPP of humiliating the NDC – had he only waited a few more moments and informed the Director of Protocol, the situation would have been redressed.

Be that as it may, Bagbin phoned his driver to come fetch him at the back entrance to the parade grounds. It had just turned 8:00 am, and he had already made off without much ado. That afternoon, as an alternative to the protest which had been prohibited, the Committee for Joint Action organised a conference at a hotel, in which many of the NDC’s top politicians were to participate. After this, Bagbin was scheduled to attend a meeting with representatives of the US Congress’s Black Caucus and other political friends from abroad at the home of the NDC flag-bearer Atta Mills, a meeting to which I was not to be granted access. Thus, it no longer made sense to continue with my research strategy, and so I wandered along the stands, sufficiently legitimated by my press pass, and like the press and television crews followed subsequent events from there.

At the entrance to the VVIP area I met the Chairman of the CPP (the new Convention People’s Party), Dr Delle, an old acquaintance from Upper West Region, complaining stridently that he too had been barred from the grandstand:

Government is saying we are not cooperating with them, but how can they say this, and ignore us! We have worked together... it seems that they don’t have any respect for us. … One of the security officers told me: ‘Well, go back comfortably to your room and watch the ceremony on TV’. … The protocol arrangement was not well done. Because whatever the case, they should have got a place for the Majority and the Minority Leader. ... Government should have started making the arrangements three years ago, ... in consultation with the political parties. … I don’t know how they will be able to answer this when they go back to Parliament, when the Minority Leader himself has been kept out, it’s terrible, it is very embarrassing.'

Shortly thereafter the Minister of State Kwadwo Mpiani, who was responsible for the festivities, appeared, and Dr Delle along with several other of the minister’s ‘acquaintances’ were hushed through the back entrance and into the elevator that took the guests up to the grandstand. I, however, remained below and, like the journalists, watched the events at close hand, engaged in a game of cat-and-mouse with the security guards over who got the spots with the best view as the Ghanaian Armed Forces, the police and the fire brigades, the cadet schools and many others who every year march in the Independence Day parades filed in.

This year, the biggest round of applause went to the kilted Pipes and Drums of the First Batallion of the Scots Guards, which the Duke of Kent as their regimental colonel had flown in from Muenster, Germany, as a sort of gift to his hosts. Following the entrance of President Kufuor and his guests – on schedule at 9:00 am – the national pledge was recited, the guards inspected and the ‘perpetual flame’ lighted at the Independence Monument. Numerous splendidly dressed chiefs filed past the podium on which the President stood and offered their greetings. With the traditional pouring of libation by some Ga elders to invoke the protection of local deities and the recitation of Muslim and Christian prayers religious diversity and ‘unity in diversity’ were enacted, a display which is an integral part of all such events in Ghana. Afterwards there were gymnastic performances by various groups of schoolchildren who had practised since months for this day, and military units marched in various formations. Then came ‘trooping the colours’ with which my Ghanaian counterparts were quite familiar and on which they commented knowledgeably. However, with the heat, the unbelievable din and the crowds, I registered little more than a whirl of visual and acoustic impressions.

I thought about how I would be able to achieve the special perspective with which I set out and finally asked a policeman where the NDC faction was sitting. Obligingly he not only led me to the appropriate section in the stands, but also waved over Atta Mills’ special assistant, who immediately had me whisked through the barrier and up into the stands. So there I was, face to face with the NDC’s presidential candidate and his associates. I introduced myself, as far as this was possible given the noise, and reported what had happened to Bagbin that morning. I was finally seated next to Deputy Minority Whip Akua Sena Dansua. Like the other NDC parliamentarians they, too, along with Bagbin, had tried to gain entry to the grandstand without avail. However, they ultimately found their own way to the stand where seating had been reserved for parliamentarians. According to Akua Dansua, even NPP members of parliament had not been allowed to sit in the grandstand, but this should have applied only to normal MPs since ‘it’s very wrong for the Minority Leader to have to beg for a place’. But on the other hand, she was thrilled by the immense turnout and commented into my dictaphone:

We want to celebrate Ghana’s independence, that is why we [NDC members] are here. We are happy about our independence, we are proud! ... The Ghanaians are all here despite the improper way it was organised, but we are here because of the love for our nation. ... It’s just wonderful to see Ghanaians from all walks of life, no matter their political organisation or their tribe or religious affiliation, coming together to commemorate this occasion. And I wish that we, that the nation, could build on the spirit of today.

The enthusiasm expressed by Akua Dansua and NDC MPs and politicians sitting near us, however, hardly extended to the speeches which were given starting from 12:00 pm. The Nigerian president in particular, whom Kufuor addressed as ‘my brother’ and to whom he would a few days later award the nation’s highest honour, the Order of the Star of Ghana, was subject to biting criticism.[13] A number of those with whom I spoke felt he should have been uninvited, since just the week before the Nigerian government had expelled several Ghanaians from their country. And during President Kufuor’s long speech, in which this time he did welcome Kofi Annan and included a few Northerners in his commemoration of heroes and founding fathers of an independent Ghana, but mostly praised his government’s accomplishments, the members of the audience around me all listened politely, but left the enthusiastic waving of flags to the NPP faction sitting in the adjacent section. In the stands, where the masses were seated, the speeches were drowned out anyway by Mexican waves and constant cheering. As Atta Mills, who under the watchful eyes of a team of journalists clapped, if rather reservedly, following the presidential speech, explained to a BBC reporter:

We are here to pay respect to the people who have contributed to make the celebration possible. We are here to pay respect to the children who have spent months rehearsing. We are here also to acknowledge the fact that for nineteen years, out of the fifty years, some of my colleagues and I were in charge of the state called Ghana, and some lost their lives … and it is to pay respect to all those who have contributed to what Ghana is now. And I am here also as a Ghanaian. Whilst we celebrate, it is also an opportunity to look at the past and the future of the nation. ... We are here to remind Ghanaians: we are only fifty years, there is a long road ahead. And it is not as rosy as people want us to believe. But I think we should remind ourselves where we have come from, where we are now and what we need to move forward as a nation. ... We have won independence, but that is not all. ... This country is disunited, it is polarised, and we do not want to admit the truth, we have corruption, we have all kinds of problems, but we are celebrating independence, because it is a fact. But where do we go from here? We should acknowledge our joint obligation.

As the official programme was coming to an end with the ‘colours march off parade’ more and more young people began gathering in front of the barrier blocking the stand where Atta Mills and the rest of us were sitting, and cheered him on. Another interview followed, but was interrupted by the singing of the national anthem and the exit of President Kufuor. Now that the event was over, many of the NDC and NPP members of parliament, who had been sitting in separate sections, greeted each other quite warmly, extending wishes of a happy Independence Day. ‘This is like in Parliament’, commented my neighbour Dansua, ‘we fight each other fiercely during sittings, but afterwards we are quite friendly...’ – like the night before it was apparent that parliamentarians share a sense of community which to some degree reaches across party boundaries.

Shortly after 1:00 pm the audience and guests all began to jostle towards the parking lots and busses. It was practically impossible to make headway, and I was impressed at how Akua Dansua, onto whom I had latched, ploughed through the masses using her sharp elbows. Akua wanted nothing more than to go home, put up her feet and most likely not attend the state banquet, like practically everyone else from the NDC. With her I drove back to Parliament, and received a phone call from my original ‘informant’ that he was still with Rawlings and the other guests, but that we might be able to meet that evening.

So I had some time off which I used to visit my Ghanaian brother from Upper West and his wife who live near Parliament House. They had spent the morning at an Independence Day mass in Christ the King, a Catholic church, and then watched the end of the parade at home on television. Now they were sitting in their garden, dressed in their Independence Jubilee t-shirts, drinking beer. Later that afternoon they planned on driving around the city to have a look at the various street festivals. Together we rang up Alban Bagbin, who knows my brother quite well, as all prominent members of the educated elite from Upper West know each other. Although my brother had once run for the NPP, he congratulated Bagbin on his speech during the Commemorative Sitting of Parliament the night before, since regional affiliation is often more important than party membership. The two of them then joked about the events that morning and wished each other a happy Independence Day.

The Golden Jubilee Parade, 6 March 2007: celebrating Ghana ‘unofficially’

Around 9:00 am, my (Jan Budniok’s) friend arrived at our meeting point, a bar in Labone, accompanied by his children Edwin (eleven) and Katrina (eight) − all of us were dressed in the Northern regional costume, the smock. I had not known in advance that this would be a family outing. The day therefore promised to be less politically charged than I had hoped, although my friend’s frequent phone conversations with politicians, would-be politicians and relatives did provide some insight into his political involvement and gave brief impressions of the course of festivities in various regions around Ghana. But as it turned out, celebrating Independence Day as probably thousands of other Ghanaians were − going on family outings, visiting bars, watching events on television or listening to the radio – was quite enlightening. Particularly interesting were the commentary and discussions amongst friends and strangers and the networks which were mobilised in the exchange of congratulations and news. My friend incidentally told me that he had actually thought about leaving Accra to celebrate Independence Day in his home region. My request to ‘shadow’ him during the festivities seems to have influenced his final decision to stay in Accra.

It was Edwin, my friend’s son, who insisted on our first destination: Independence Square and the Golden Jubilee Parade. Approximately three-hundred meters from the square, hundreds of people were flocking through the streets towards Independence Arch, waving Ghanaian flags, flashily dressed in Ghana@50 t-shirts and caps. The small car park in front of Osu cemetery was the nearest parking available. My friend pushed his way ahead, holding his kids tightly by his side. Behind Independence Arch, we found ourselves surrounded by a seemingly impenetrable crowd. Yet our attempts to reach the edge of the crowd to catch a glimpse of the parade were constantly frustrated. But what we could see was that the platforms surrounding the square cramped with revellers all decked out in some form of the Ghanaian flag: some simply waving small flags, others draped in large versions of it and yet others almost completely body-painted in the colours.

While we tried to get to the left side of the square and to avoid being crushed by the buoyant masses, a sudden rush surged through the crowd, forcing some one hundred people into the gutter. To the left we noticed that not only were the stands filled with twice as many people as there were seats, but that the space in between was also packed with crowds. We were told that the happy few tens of thousands who had managed to snatch seating in the stands had done so in the early morning hours. Finally, we headed towards the back of the square, walking behind the stalls where kebab and other dishes were prepared on grills and fresh water sold. At 10:30 am we reached the back of the square and spotted the press box surrounded by people struggling to get nearer to the barrier to catch a glimpse of the parade. Since I had been given a press pass, I tried to enter with the children, but security would not let them in without a pass. Having entered the press box alone, I had a good look at the parade and took a few pictures, but soon rejoined my friend. We walked along the back of the square, just behind the Presidential Arch, where we met the NPP member responsible for youth activities in the Accra Region dressed in jeans and a Ghana@50 t-shirt. We shook hands and exchanged congratulations for such a splendid day. The back was less densely packed than the front of the square. My friend and I each carried a child on our shoulders. After having spent the last one-and-a-half hours trying to catch a glimpse of the parade, like ninety percent of our fellow spectators, we finally spotted the soldiers marching past. My friend took a couple of photos of the children, and from our new position we had a clear view of the Presidential Arch, where several African presidents and other dignitaries were seated in the grandstand high above the crowd. My friend tried to explain to me the who’s-who amongst the President and his cohorts.

We left the arch, moving towards the gate between Independence Square and the beach, along which there are watchtowers and which on this special day was protected by armed soldiers and tanks. Some ten thousand people had come to the beach, only a few hundred metres from the parade, perhaps because they were unable to see it. In the distance, the navy was patrolling the coast, and on hundreds of carts vendors were selling food. Finally, we bought some Ghana@50 badges. At 11:00 am we were on our way back to Independence Arch. From afar we could hear scattered bits of the presidential speech while we walked along the safety wall, over a gutter and back to the street. In front of the construction site of the new football stadium we ran into Imorou, a filmmaker, happily giving money away to some children. Meanwhile, the Ghanaian air force flew over the square, the jets making a great impression on the cheerful crowd as they sky-painted stripes in the national colours. I was complimented on my smock which I inwardly cursed as I was sweating. We threaded our way through the crowded street carnival peppered with vendors selling Independence-Day paraphernalia and souvenirs, food and drinks. Around Independence Arch, people hosted their own spectacle, a hundred metres away from the official parade, some in fancy ‘patriotic’ outfits, others dressed as devils, and many were dancing, radiant with joy. Once again, I hoisted Edwin on my shoulders so he could properly see the brass bands, clowns on stilts, decorated horses, and saluting cannons. Some spectators climbed trees to get a better view of the colourful goings-on, others positioned themselves on top of nearby ministerial buildings, and even the top of Independence Arch was packed with people.

Finally, after I took pictures of my friend and the delighted kids posing in front of the now colourful Independence Arch, we went back to the car and left Osu cemetery around noon. While driving we discussed our first impressions of the Jubilee Parade. The conversation turned quickly to the President’s dress, a matter extensively discussed in the press both before and after the parade. My friend sided with the President who had argued his suit was a fitting symbol for a modern Ghana and that on similar occasions the heads of state of nations like China or Japan would also choose to wear ‘modern suits’. However, the appropriate dress code was controversial for further reasons: many people had noted that the television spot which had been running since the beginning of the year in order to rally Ghanaian spirits for the celebration clearly showed Nkrumah and his close associates declaring independence at the Old Polo Grounds clad in Northern smocks (only the next day, during the first session of the independent Parliament, did Nkrumah and his cabinet sport kente cloth, thus carefully balancing regional identifications). My friend then also complained about the miraculous re-clothing of the Nkrumah statue. When the monument stood in front of the old Parliament House, it showed Nkrumah in a smock. But after the statue had to undergo repair following the breaking off of one of its arms during its relocation to Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park in 1992, Nkrumah re-appeared dressed in kente cloth. But at least he wore ‘Ghanaian costume’. In contrast, President Kufuor’s choice of the suit for the Jubilee Parade attracted much scathing criticism. Although his predecessor Rawlings did choose to wear Ghanaian costume, he was also criticised for his inability to wear the Akan cloth in the traditional manner with the required dignity. But now in retrospect, he is praised for his preference for Ghanaian clothing, and his versatility in alternating between the Northern smock, the Muslim boubou, the kente cloth, etc. Kufuor, often seen in a Western suit, compares poorly in this regard. During the Commemorative Parliamentary Sitting, Kufuor did wear a light-blue boubou, but observers criticised it as being inappropriately simple for the occasion. On the other hand, at least it was ‘Ghanaian’, unlike the suits he and some of his cabinet ministers wore on March 6, a choice which many regarded to be a ‘shame’ to the nation. Kufuor himself argued the suit was appropriate to receive state guests and was simply more comfortable than the cumbersome cloth. The presidential Jubilee dress code has occasioned so much debate (also in blogs and feature articles on the internet) that some critics have asked whether this topic really warrants so much discussion, whether there is anything really uniquely ‘Ghanaian’ about the kente, and why the President should be criticised for wearing Western clothes when ordinary Ghanaians have no qualms about driving fancy Western cars or putting permanents in their hair. However, the matter is anything but trivial: the question of appropriate clothing has attracted so much attention because it has become an idiom in which the role ‘tradition’ and regional identity in the modern nation is debated.

At 12:30 pm we returned to the very bar from where we had set out that morning. The barkeeper was still listening to the live coverage of the celebrations on the radio. Barely fifteen minutes later we were served our second bottle of beer and examined the photos we had taken at Independence Square. Meanwhile, my friend telephoned with colleagues, politicians, friends and kin. He had missed several calls while we were walking around the Square, and even more people were trying to ring him now. I inquired later where most of his colleagues had spent the day. Many members of the elite who had no official function in the parade or in any other event attended festivities in their home towns or followed the ceremonies on television. They exchanged their impressions of the events and congratulated each other, talked about national and local politics, by-elections and the election of the NPP presidential candidate. A brief chat with a former minister of finance was followed by calls from district chief executives, telephone conversations with some NPP regional secretaries, the NPP Vice-Secretary of the Upper West Region and a young member of parliament who had travelled to his constituency and attended a function in Tema stadium. Some phone calls were also made to family, friends and acquaintances in his home region.

At 2:00 pm we set out for the Ghana International Trade Fair, only to be immediately caught in a traffic jam in an area where at this time on any other day there would be no traffic at all. While driving, we again passed several luxury cars filled with foreign dignitaries. When we arrived at the spacious trade fair grounds, hundreds of people were lined up in front of the main entrance, and the line was just as long when we left the exhibition in the evening. We drove into the back entrance, while Edwin sang the Ghana@50 anthem. Festive streamers, designed in much the same style as the Ghana@50 banners, and in some instances even sporting both logos, were hung across the streets in honour of the Trade Fair@40. A short distance from the parking lot we tasted fresh cocoa drinks at the stand representing the cocoa industry, which as if by a miracle was celebrating Cocoa@60. While we enjoyed our cocoa drinks, we listened to a detailed lecture on the varieties of cocoa beans and their economic value − the one cash crop on which much of Ghana’s early wealth had been based and which was intimately related to the achievement of independence. Later, we took pictures of the children posing next to an artificial cacao tree on display in a small cocoa museum which paid homage to the cocoa bean as the source and a symbol of the nation’s wealth.

The vast fair grounds and exhibition halls were crowded with visitors admiring the various stands displaying cooking pots, cloth, wigs and hair pieces bearing the nation’s colours. On this day the trade fair was not just a trade show and an exposition of consumer goods, from the latest electronic gadgets to simple cocking pots, but a festival. Classes of schoolchildren and families roamed about. People met friends and family, ate and drank plenty of beer and soft drinks, wearing Ghana@50 clothes, clearly celebrating Independence Day. The fair grounds thus literally became something of an extension of the festivities at Independence Square, except that here it was less crowded and so more convenient for families. After one-and-a-half hours, we rested under a tent, surrounded by a cheerful crowd, drinking and eating, and we joined them in enjoying another generous round of beer, kebab and popcorn while looking some more at the pictures on each others’ digital cameras. Some people from my friend’s home region, Nandom, joined our group and began to discuss the work and progress of their fellow people. Then I was in for a pleasant surprise when my friend introduced me to David Dontoh, the actor who had played Nkrumah the day before on the Old Polo Grounds, and who apparently is an old acquaintance of his.

At sunset we again joined the queue of cars inching their way along the main road. Judging by the traffic, it seemed that not all of the better-off had stayed at home to follow the festivities on TV but visibly celebrated the day in one or the other place in Accra, and families, in particular, had obviously opted to enjoy their day at venues other than Independence Square, venues such as the trade fair at the fairgrounds.

Final Reflections: chilling at ‘Tina’s Cool Spot’

In the evening, regional friendships prevailed over political loyalties. We met our informants and some friends for a beer at Tina’s Cool Spot, a bar which for a number of years has been a popular hangout for Upper Westerners. Here, our two informants, the NDC and NPP politician, often meet to discuss recent political developments, and it was here that all had gathered in honour of Independence Day. A number of acquaintances had already spent the entire day here watching the festivities on television. Actually it was an evening much like any other at the bar, except that some customers were wearing patriotic t-shirts or smocks made out of Jubilee cloth and that it was perhaps a bit noisier than usual.

The day’s events were now debated less heatedly than one would have imagined given the vigorous debates that had taken place amongst the parties during the previous weeks. It remained contentious whether Ghana@50 had been an Accra event or whether the grass roots and the regions had been sufficiently included. Doubts were also raised whether an organisation like the government-affiliated Ghana@50 secretariat was effective and transparent and whether it really should organise the African Coup of Nations (CAN) 2008, as had apparently been planned. Should the organisation not have involved the opposition parties right from the outset? In any case, everyone was relieved that during the festivities no one had donned party logos or t-shirts and that national symbols predominated. Thus most people felt the festivities had united the nation across party lines and strengthened national unity, although the debates spawned by the celebration will, like the festivities themselves, continue throughout the year and so continue to preoccupy our friends and the Ghanaian public.

Yet despite all the controversy it became quite patent that the debate was governed by a number of partly explicit, but mostly implicit shared understandings and ‘conventions’ that define Ghanaian-ness. These commonalities rest not so much on substantive symbols, cultural traits or other ‘objectifiable’ characteristics. Rather, Ghanaians tend to agree on the importance of the issues at stake and on the rules of the debate, defining Ghanaian-ness in reference to the respect for these basic rules of civility. The desirability of political diversity and ‘multi-party’ democracy is part of the consensus of what should define the nation’s future, and, even more importantly, Ghanaians agree that disagreements should by all means be resolved (or tolerated) without recourse to violence. ‘Unity in diversity’, with regard to both politics and ethnic-regional diversity is more than just an official slogan, it is a widely shared conviction. Yet how precisely this maxim is to be realised is controversial, but such controversy in turn strengthens national consciousness and deepens a sense of commonality.

References

Ayensu, K. B. and S. N. Darkwa, 1999: The Evolution of Parliament in Ghana. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

Nugent, Paul, 1999: Living in the past: urban, rural and ethnic themes in the 1992 and 1996 elections in Ghana. Journal of Modern African Studies 37: 287−319.

Nugent, Paul, 2001: Winners, losers and also rans: money, moral authority and voting patterns in the Ghana 2000 elections. African Affairs 100: 405−28.

[1] We would like to thank the VolkswagenStiftung for their financial support of the research project ‘States at Work: Public Services and Civil Servants in West Africa: Education and Justice in Benin, Ghana, Mali and Niger’ that made our work in Ghana possible. Thanks also go to the Honourable Alban Bagbin, Honourable Akua Sena Dansua, Dr Sebastian und Stephen Bemile, Honourable Dr Ben Kunbuor, Aloysius and Kafui Denkabe, Herbert Kongwieh and all other Ghanaian friends and colleagues who assisted us in our research on the Independence Day Celebrations. Finally, thanks go to Katja Rieck for her competent services in copy editing the text.

[2] The official programme can be easily accessed via the internet, at the webpage of the Ghana@50 secretariat: www.ghana50gov.gh/ghana50/index.php (last reviewed 12 Sep 2013, no longer accessible). Many foreign institutions, too, participate in one way or another in Ghana’s independence celebrations; for the German contribution to the festivities, see the Jubilee webpage organised by the German Embassy, http://www.ghana.diplo.de/Vertretung/ghana/en/Startseite.html (last accessed 12 Sep 2013, content no longer available).

[3] ‘Reconsider decision to boycott sittings’, Daily Graphic, 9 Feb 2007.

[4] Press release by Jerry John Rawlings on 5 March 2007, published on the internet at: http://www.modernghana.com/GhanaHome/NewsArchive (last accessed 12 Sep 2013, exact address http://www.modernghana.com/news/124909/1/rawlings-will-not-attend-ghana50-programmes-press-.html (accessed 12 Sep 2013)).

[5] The Old Polo Grounds housed one of the prestigious British sports clubs, and Nkrumah’s choice of this venue for his declaration was, of course, of great symbolic significance. It was here that the Rawlings government built, in the early 1990s and with the help of Chinese grants, the Kwame Nkrumah Memorial Park and houses, among others, the Nkrumah mausoleum. The Parliament was relocated to a new building at some distance from the Old Polo Grounds in the 1990s.

[6] For more details on the 1957 organisation of events, see e.g. Ayensu and Darkwa 1999.

[7] The offices of the Presidency, Vice-Presidency and some cabinet ministers are housed in one of the old slave castles on Accra’s shore, and the term ‘Castle’ is often used as a nickname (like ‘White House’, etc.).

[8] ‘Ghana@50 – Time to believe in ourselves’, Daily Graphic, 24 May 2007.

[9] ‘Ghana flags being stolen’, http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive General News of 4 March 2007 (last accessed 12 Sep 2013, exact address http://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/artikel.php?ID=120250 (accessed 12 Sep 2013).

[10] On this cf. Nugent 1999 and 2001.

[11] See, for instance, ‘Independence Declaration re-enacted’, Daily Graphic, 7 March 2007.

[12] This however did not correspond to the official press statements later made by the NDC, in which the NDC Chairman, for example, criticised the inadequate organisation of events, but then went on to expressly praise the ‘impressive nature of the large crowd which attended the parade’; ‘Reactions to Jubilee celebration’, Daily Graphic, 12 March 2007.

[13] See the report ‘Ghana honours Obasanjo’, Daily Graphic, 8 March 2007.

© Oluniyi Ajao | flickr CC BY 2.0. Titel: Ghana's 50th Independence Anniversary national parade. (Golden Jubilee)

Ghana@50 – celebrating the nation

An eyewitness account from Accra