In many ways, photography is right at the heart of Maaza Mengiste’s work. She is a photographer herself, and an avid collector of photographs. But most of all, she is a writer who has turned to photography as a source of both inspiration and critical inquiry. Her latest novel, The Shadow King (dt. Der Schattenkönig), which was shortlisted for the prestigious Booker Prize in 2020, is set in Ethiopia in 1935, when Mussolini’s forces set out to colonize the only independent East African country. Mengiste takes on a prismatic approach in exploring the manifold repercussions of the Italo-Ethiopian War on the individual lives involved in it. But a specific focus is placed on the experiences of Ethiopian female soldiers, whose histories have been largely left out of the public memory of the war. Photographs have led her along that way. While researching for The Shadow King in Italy, Mengiste found countless private images and albums from the war. Some of them have made their way into the novel, as “orphaned” portraits of women she came across evolved into leading characters in her work. But her collection soon exceeded the scope of a single story. In 2019, Mengiste initiated project3541, a photographic archive of the Second Italo-Ethiopian War, that seeks to provide “an intimate perspective on the global and personal consequences” of the conflict. More than conserving documents that have remained outside of the official archives, it seeks to invite educational and artistic interventions with the aim of enabling a more personal and inclusive conversation on the war and its long-lasting effects in the Ethiopian and Italian population. Mengiste was born in Addis Ababa and spent the early years of her childhood in Ethiopia, until the Revolution forced her family to flee their home in 1974, first to Lagos, then to Nairobi, and finally to the United States. As a novelist and essayist, whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Guardian, Granta and The New Yorker, she has continuously returned to Ethiopia to reflect on its troubled histories and the ways they are represented, and neglected, in the present. For the last twelve months, Mengiste, who regularly teaches English at Wesleyan University in Connecticut, held a DAAD Artist-in-Berlin Fellowship.

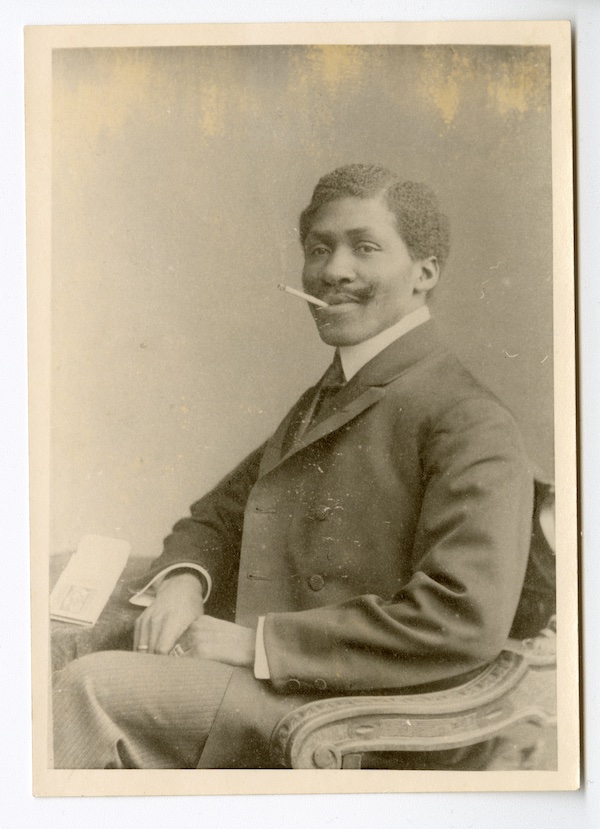

We first met at the Schöneberg Museum, which currently features an exhibition on a Black family that has lived in Germany for five generations. It starts out on Mandenga Diek, an aspiring young man from Douala, then capital of Cameroon, who arrived in Hamburg in 1891 with the hope of studying medicine. Upon realizing that the sight of blood was too disturbing, Diek swiftly changed paths and became a professional shoemaker. When the shop owner, well aware of the potentially lucrative curiosity of a dark-skinned employee, ordered Diek to work from the shop window, he quickly escaped the exploitative environment and moved to Gdańsk. He opened a general store, and soon established himself as a successful and well-respected businessman. In 1896, Mandenga Diek became one of the first native Africans to be granted German Citizenship.

All of this we learn later on. The exhibition’s opening visual sample, however, is a photo of Diek from the 1920’s, long after he had moved to Gdańsk. He is dressed in a fine suit. His hands are elegantly folded in his lap, in a way that allows us to see two gleaming rings. His posture is composed, but not idle, his left elbow lifted just slightly above the armrest. With a side-parted hair and an upswept mustache, Diek appears charming and confident. It is a studio portrait, well in line with the ideals of bourgeois representation of the time.

But it is the cigarette in the corner of his mouth that caught Maaza Mengiste’s attention. Curiously, it turns upward, lending Diek’s formal pose a sense of irony. It is details like these, small moments of irritation, that spark her interest. “They are like clues that can lead to a whole new story”, Mengiste told me two weeks later in a café nearby to talk about how photography affects our understanding of the past. “Coming from somebody who did not want to be made a spectacle, this is him saying ‘You look at me the way I want you to. But you’ll look at me.’”

Robert Mueller-Stahl: I‘ve noticed that in your work, photographs often seem to be spurring the story. The characters are being called to action by pictures they see. What do you think it is about photographs that moves people?

Maaza Mengiste: I think photographs are our way of saying “I was here and this is what I saw. I was here and this is me in this place.” It’s a marker of presence, it’s a way to say “I exist right now.”

They are very similar to those ancient cave drawings, where there are sketches of a cow, or horses, or the sun, and you might see a human. Those drawings were meant to say “This is what I see. This is what I do, this is where I am.”

It’s an extension of that very limited vocabulary of a drawing, where we know there was more going on, but that’s not what’s rendered onto stone, it’s not what’s shown. I think this is what a photograph is supposed to be.

It’s a way to curate memories, not to confirm, but to reshape, and to retell them. Photographs can make an absolutely horrible family gathering look like the most joyous thing ever happened. It depends on the photographs you take. These photos can really reshape history. They can reshape individual memory.

What do you look for in a photo? How do you approach it?

For me, photographs are really just the first step in trying to understand the moment. Because they lead me to a first question: What is happening here, why was this made, what else is going on. Why does this photograph attempt to deny that, or signify that particular moment? Photographs are a way for me to step into a moment.

Let’s talk about your archival endeavor, project3541. How did it come together?

For my book, I did a lot of research in Italy. I went to flea markets, used bookstores, antique stores. People sent me photographs. And at some point, I wanted to create some kind of a database, some kind of collection, so that people can go back and maybe gain some kind of understanding of that history.

So I’ve started posting just a few of the photos I have online and I’m slowly developing this site. I’m very careful and protective with them. I feel that they are real people. But we have to share, so I’m thinking of ways to collaborate, to make it interactive. I want people who have photographs and have stories to have a place where they can contact me or share their photographs and whatever memories they may have.

Who took all these photos?

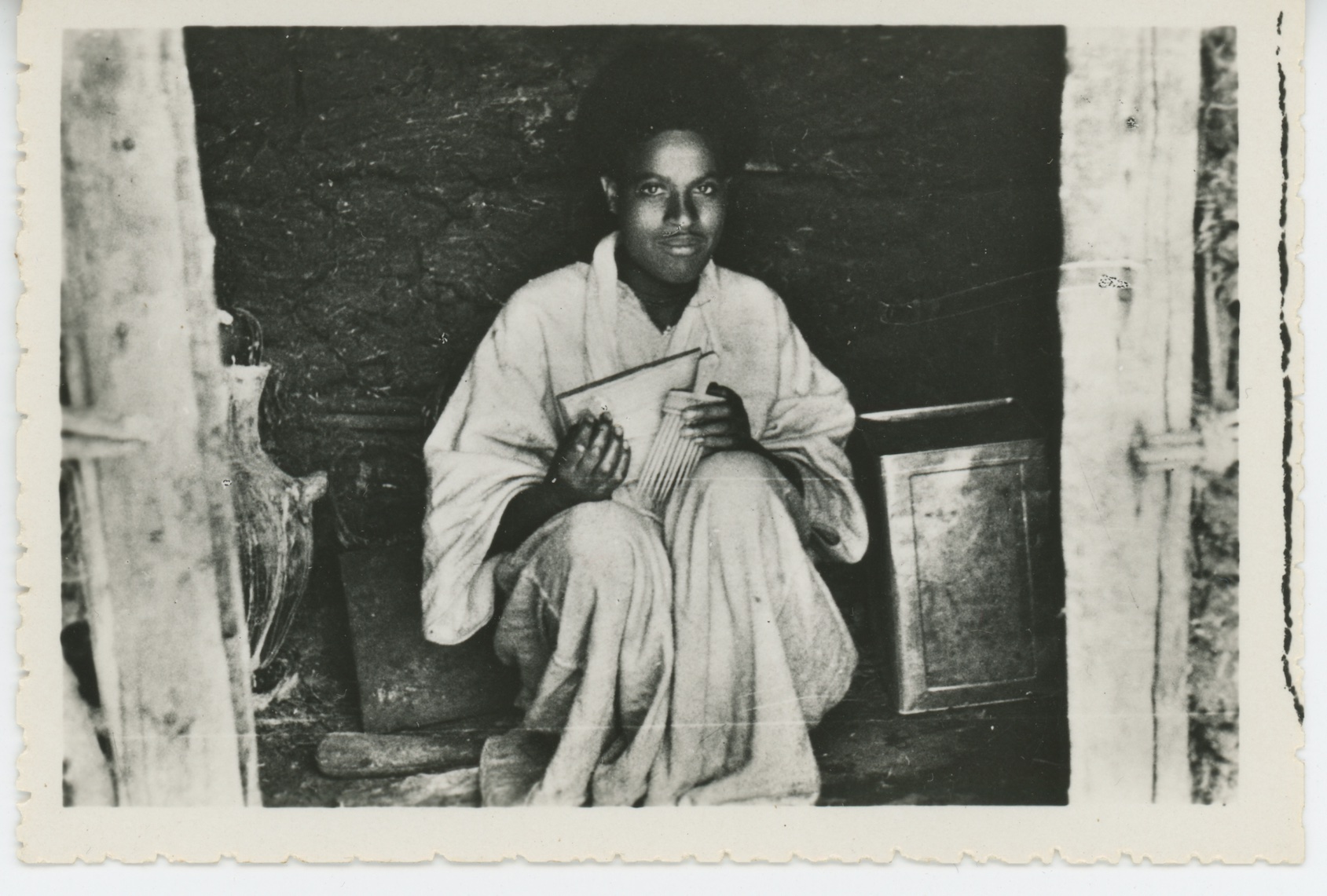

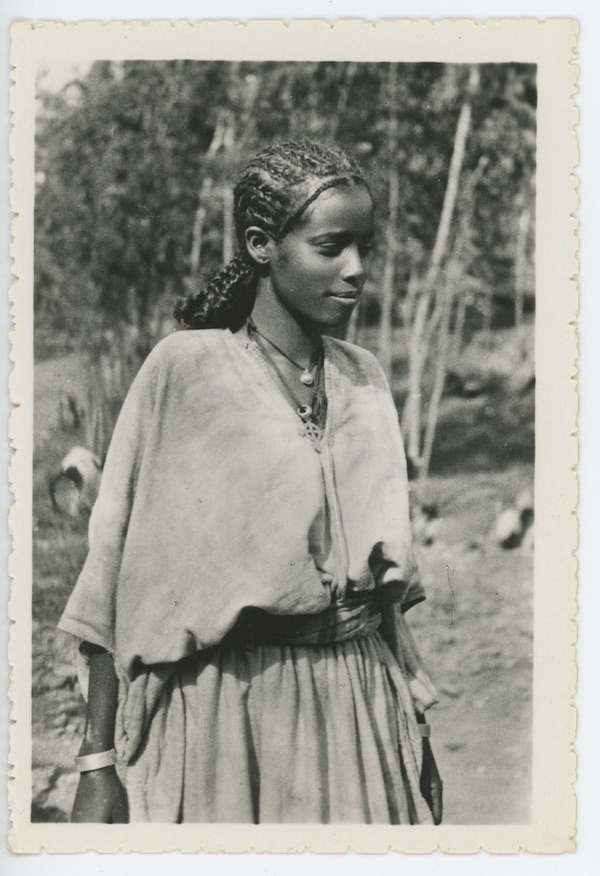

The interesting thing about this is that Italians were the ones that had the cameras. They were the ones who made photographs of East Africans. And what I’m looking for now is the stories that have come from the Ethiopian or East African side. So I’ve created a page that’s called “Memories without Faces”. I’m getting some of those things together and hoping that people will interact and add their own stories. That way the site can grow.

So all the photos in the archive were shot by Italian men?

Yes. They traded them, sometimes for cigarettes, or made them into postcards.

But there is no hint at their presence in many of the portraits. Take, for example, the photo of a women in a white dress. She’s holding a rifle. How do you explain this?

This is an interesting case. The first instinct is to say: She’s really proud, this is a warrior.

But the photo is in an album by an Italian soldier, which is full of photos of women, and all of them are naked. So this is all exploitative. Every single one. And then you see her, with the gun. But if you consider the other images, you realize that the picture is mocking her. The gun is his gun, it is the soldier’s gun. And so that photograph is making fun of her, it is stripping her in a different way. For him, the photo is another trophy to take home with him.

The context here is very critical, too. It was taken in Debre Birhan, in 1937, at the height of the battle. In February of that year, Italian soldiers carried out a massacre, killing thousands of people. It started out in Addis Ababa and extended to other towns, including Debre Birhan. But it is also a time when Ethiopian guerilla fighting increased. Italians were ambushed all the time. Maybe the photographer was taking this image to remind himself that he could still control something, in addition to these naked girls.

But for me, her look is even more interesting. She is comfortable in that moment because seeing an Italian is not a new thing. And she is comfortable holding the rifle because by 1937, practically every Ethiopian woman knew how to carry a rifle. Women who are exploited, even in that moment of exploitation can still find strength. And that, to me, is signified in that photograph.

Private photography is often considered conventional and mundane. But you seem to think of it as a contested source of self-assurance.

I’m thinking about Victor Klemperer’s journals. As his world became more and more narrow and dark, he continued to write and note down what he saw happening around him, and to the German language in the Third Reich. He wanted to bear witness, so that in another world his voice and vision could matter again. So in his work, there is an insistence on a kind of recognition, on the possibility of being recognized on his own terms. The women in these photographs were not the ones taking the pictures, but they are doing a similar thing. In that moment, they are still exercising some kind of control.

I’m glad you bring this up. Taking photographs serious has deeply unsettled my conception of history. It is as though they defy our expectations. We know about the context of persecution, but it’s left out of the frame. What do you make of this?

We’ve learned to think of photographs as stopping time, which is stopping death. Photography has been so closely associated with the end of something. We don’t ask what continues through photographs. They are reaching towards a future, a kind of life that is possible. There is an insistence on being seen the way they want to be seen. There is an insistence on hope.

Maaza Mengiste, The Shadow King, WW Norton & Co 2019, 428 p.

dt.: Der Schattenkönig, dtv 2020, 576 S.

The exhibiton “Auf den Spuren der Familie Diek. Geschichten Schwarzer Menschen in Schöneberg“ runs until 15 October; Saturday to Thursday, 2 – 6pm, Friday 9am – 2pm, Schöneberg Museum, Hauptstraße 40/42, 10827 Berlin, free entry.

Zitation

Robert Mueller-Stahl, Stepping into (a different) Tomorrow. An Interview with Maaza Mengiste on defiance and hope in private photographs of the Italo-Ethiopian War 1935-1941 and beyond , in: Zeitgeschichte-online, , URL: https://dev.zeitgeschichte-online.de/themen/stepping-different-tomorrow